Growing up I loved learning and had an intellectual curiosity. But school was not my thing. I was a terrible student. As an adult, I reflect back to my childhood state of mind to try to figure out why I received such poor grades.

I devoured the computer and everything it had to offer. Hours upon hours were spent tinkering and building and breaking concepts that were well beyond those of my school’s curriculum. There were no boundaries or arbitrary divisions, only many questions and resources to answer them. And nothing inspired me more than unanswered questions so answer them I did!

So why then did I fail at school?

Is not this intellectual curiosity the key ingredient for a budding young mind?

What went wrong?

The zeitgeist of the 90s sent mixed signals. On one hand, we had a hyper-refined post-industrial Western world operating at the fevered peak of its wildest, oil slicked dreams. On the other, we had the Internet delivering chaotic, novel and unstructured information at a torrential pace.

While the devastating fruits of industry are clear in our heat and light, vehicles, food and devices, the impact of the early Internet years on our collective psyche is still more profound. Only now in the year 2020 have we started coming to grips with what it means to forever be coupled through a dynamic and hyper-connective permanent record of ceaseless intelligence.

Back at school in the 90s, teachers gift their students refined stacks of paper containing formal, structured studies. At home, a search engine provides limitless access to unfiltered ideas, unimaginable in depth.

Psychologist Carl Gustav Young once described the ego, an individual’s sense of self, as a cork bobbing on the endless ocean that is the collective human subconscious.

The Internet itself became analogous to Jung’s ocean-like collective unconscious. But instead it became conscious vastness, alive and able to be explored. And compared to it, school curriculum became the new cork.

This is to say that what we were supposed to know, what we were taught to know became a tiny sliver of what we could know, what we all now know. And like the deep collective psyche that tethers us all together, we were expected to ignore this truth and stay confined in our cork, our prison.

School suggested life was one way, but all of it, all the screaming human madness blasting through the phone line’s dial tone into the computer, convinced me that there was more to the story. Yet school kept the tale going. It refused to drop the act. And how could it?

How can a cork teach of the ocean, the collective and cathartic deposit of millions of years of evolutionary mind-madness? You cannot judge it. You cannot grade it. It is beyond us all. You cannot teach it. You learn to ignore it, stay in your vessel and bob. Or you learn to embrace it.

Each person who broke off the rails and embraced the depths of the early pre-aggregate Internet felt the separation. It was agony, a stark disassociation that felt right, yet was not at all understood by our authorities: governments, friends, families, teachers, elders.

All relations become tenuous through this disparity, a phrenia well known by those who strayed too far into the unconscious, yet now rooted, normalized and applied to the typical lived experience. It is a new madness, shared by unmet souls scattered around the world, like stars pocked across the night sky flickering in and out of existence.

And who could tell who was afflicted with this memetic plague, who had been spoiled by the Internet? Like the cork that can not fathom the ocean which holds it and contains it, neither can the school system fathom the Internet which would overwhelm it.

How well you could be molded, how well you could restrain this vastness, aligned in rough approximation to your letter grade. This letter grade indicated the quality of your path through the institution and into the labour force and social hierarchy. Or so you were told until these ideas – like most other ideas of our proposed future – were supplanted, if not blown apart, by the Internet.

I reflect back to the core question, “why” – why was I unable to succeed in school? The simple answer is that I was not able to behave. Too much energy.

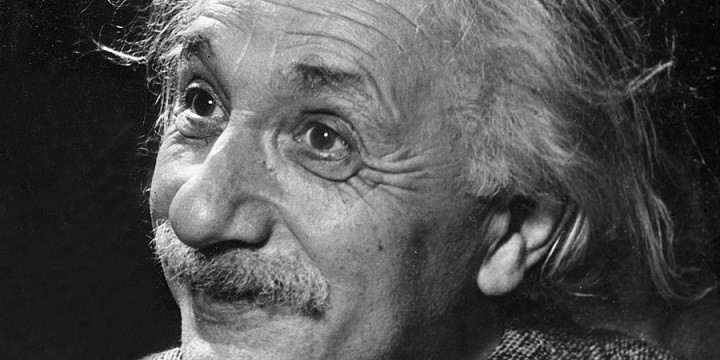

The more interesting answer comes as yet another contradiction. I recall a wild-haired face plastered around the school, the poster-man for the academic institution who paradoxically held values that undermined its existence. A rebellious mystic, hiding in plain sight behind science, mushroom clouds and cryptic mathematical symbols.

“Imagination is more important than knowledge.”

I learned much about Albert Einstein, through physics and the study of the second World War. He was everywhere. A great mind, by many considered the greatest. All I knew was that he had weird hair and he was in black and white, which meant that he was strange, old and wise and people seemed to respect him.

I had weird hair too. But I did not understand or identify with intellect and I did not – to be certain – deify it. After all, what is “smart” to a failing student but for what you are not? Even still, I believed him with blind faith and trust as the institution expects and I chose to love him for the eccentric spirit which I projected onto him.

“I believe in intuition and inspiration. . . At times, I feel certain I am right while not knowing the reason. When the eclipse of 1919 confirmed my intuition, I was not in the least surprised. In fact, I would have been astonished had it turned out otherwise. Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution. It is, strictly speaking, a real factor in scientific research.”

I can not tell you what I learned in math, sciences, social studies or any of it. But I can tell you of one single idea that won out over all others. I was a terrible student because in my heart, at the core of my being, I knew that imagination was the highest ideal.

I knew that intuition, that the things I saw when I closed my eyes, that I felt in my heart – in my “soul” – that the scenes I participated in when I went to sleep, were just as real as the rigidities presented to me at school.

I knew that whatever was in my textbooks, whatever the teachers were trying to teach me, was but a small sliver of what there was to know. All I had to do to prove this was sit in front of the home computer.

And I came to know that all of it, the collected masses of every one of the uncountable bits that these networks produce was yet smaller still when compared to the vastness of the unconscious. The Internet is its own cork, vast as it is, yet still a pale limit hiding something far greater.

“There is no universe beyond the universe for us. It is not part of our concept. Of course, you must not take the comparison with the globe literally. I am only speaking in symbols. Most mistakes in philosophy and logic occur because the human mind is apt to take the symbol for the reality.”

Einstein discovered that measurements of space and time remain the same when measured within and up to the speed of light. This proved that every physical being that is not accelerating through space as a faster than light beam perceives the same physical truth. And so as far as our flesh-suits go, this reality is real. It is the way.

But the beautiful things all around us, the unknowable things just out of the grip of our consciousness, are ever-faster than light, yet slow beyond measure, limitless, endless, right here and right now and available through the imagination. Consciousness is a cork, born from light, and so always a cork. Even when that cork itself is an ocean as vast as the ever-growing Internet, the black vastness expands in elegant accordance to dwarf it all the same.

If I were to have been taught from this book, the book that does not exist but as an ideal stretching beyond light in an irrelevant position of space and time, then I would have learned that there is much more to life than we can capture in symbolic knowledge, the plain limit of our institution.

Imagination is presence. It is more important than knowledge, more vast than knowledge, more powerful, more truthful and yet more simple and more accessible. All can revel in it, whether rich or poor, smart or stupid.

Yet we choose to keep the wheel spinning, to keep stoking the great lie. We choose to believe that virtuous conquest of the mind and enduring growth of the spirit will be found through the investigation of intelligible symbols. These symbols are allies and tools, slaves to a never arriving future and not answers. They are unable to deliver peace or salvation.

Why did I fail? Because I chose something deeper. I chose to abandon knowledge and avoid the seduction of a never-to-exist future to stay in the present. I chose to preserve my wild and creative spirit and believe the truthes I glimpsed in the darkness. The cork was to be my prison. And I wanted no part of that.

>> Home“I see a pattern. But my imagination can not picture the maker of that pattern. I see the clock. But I cannot envisage the clock- maker. The human mind is unable to conceive of the four dimensions. How can it conceive of a God, before whom a thousand years and a thousand dimensions are as one?”